A “tied house” was a type of saloon that originated in England, but gained infamy in pre-prohibition America. An institution that was believed to promote intemperance, tied houses were one of many factors leading to national prohibition in 1919. A number of former tied houses remain in Chicago, long after the practice has been made illegal. Most of the remaining buildings were tied to

Ironically, the event which led to tied houses arising saloon

Brewing companies soon realized that tied houses were a very profitable way to dump their product on the population. During the 1890’s, the number of saloons in Chicago increased dramatically. This led to increased competition and price wars among breweries. However, the cutthroat competition among the breweries had an averse affect

The negative effects of alcohol over consumption created a backlash. The tied house concept was not entirely to blame, but it was a definite factor contributing to national prohibition. After prohibition ended, the federal government gave states the authority to control beer and liquor sales. Most states instituted a “three-tier system.” Alcohol could only be sold from manufacturers to distributors, distributors to retailers. Each tier is not allowed to have an interest in the other two tiers. Thus, fair competition and moderate marketing practices were encouraged. There are some exceptions and variances to these laws, but the addition of a middleman and separation of interests in general has worked very well for

Schlitz

The Schlitz brewing company of Milwaukee was the most prolific builder of tied are

Two very well-preserved Schlitz tied houses. These two locations, less than a half a mile from each other on Southport, are likely the two most well known Schlitz tied houses in Chicago. These are well-known in part because they are located in Lincoln Park, a neighborhood now populated by the sort of people who did not live in this area during the era in which Schlitz was making Milwaukee famous. It is very likely that the influx of the post-1980s-new-monied-upper-middle-class made possible the economic conditions for the spectacular preservation of these two examples. Even the interiors are well preserved, Southport Lanes has

The globes of Southport Lanes and Schuba’s compared.

|   |

Even though the two previous examples were well preserved, neither has a stained glass window treatment. Once a common feature, the only one we have found is on the saloon at 94th and Ewing. In South Chicago, it is not a matter of active preservation, rather, a passive lack of influence from externalities difference then Schuba’s is

It must be kept in mind that these were built in a markedly different time under vastly different social conditions, and served a clientele that was more numerous in the past than now. As evinced by the positioning of tied houses at

Left: Illinois Historic Preservation Association.

Contrary to the previous examples, this building at Armitage and Damen has been re-bricked on the first floor. See how the original front door has been covered, while the cornering brickwork has been extended down? Unfortunately, the color and pattern of the new brick doesn’t even come

Left: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency.

This example, located at Division and Wood, had its dome and cupola removed, something that would not be obvious without the older photo. Now that we know these are missing, it seems glaring, giving the building in its current state an unbalanced feeling.

Left: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency.

Except for two minor alterations to the cornice and turret, this tied house at Armitage and Oakley is in excellent condition. Why is it that the most well-kept, well-preserved tied houses are bars

Left: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency.

Broadway and Winona, mid-1970s at left, and 4th of July 2009 at right. The building looks essentially the same today as it did thirty years ago, including the “Restaurant” neon-sans-neon sign. The one major alteration is the removal of the wooden detailing just under the cornice. Located in Uptown, this is one of the northernmost tied houses in Chicago. It is larger and more ornate than the rest, comparable to the 19th and Blue Island location (below). Were these were flagship locations; cathedrals

This non-globed

Left: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency.

This example, located at 11402 S. Front Street, has an interesting story. It was part of a complex of buildings funded by Schlitz; of which few remain. Located in Kensington around 115th and King Drive, the complex was built across the tracks from the company town of Pullman. Pullman was dry, built in

Left: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency.

Located on the corner of Grand and Damen, this example is in by far the worst shape of any tied house on this page. Not terribly exciting to begin with, the molding at the top was sloppily removed, as were the relief portions of the trademark globe (below). Shameful.

Detail of the globe, Damen and Grand.

Left: Located at 35th and Western, the layer of grime covering this example’s globe reflects its industrial surroundings. Aside from the absent

Right: This uniquely designed example at

This example

On a different note, Schlitz sales fell off in the mid-1970’s when they changed their recipe and method of production. The product was notoriously bad during this era, coming to be pejoratively referred to as “Schitz.” However, the brand has seen a resurgence in the past decade for those looking to get retro-drunk.

Stege & Others

Tied houses were integrated marketing schemes and chain stores all rolled into one. This was an over saturated market where brewers cut out the middle men (distributors and retailers), and pulled out all the stops in order to win customers. The high-style architecture was utilized to lend respectability to the idea that alcohol consumption could exist as part of a cultural institution. Whether or not they were effective, these buildings decorated what would may have been undistinguished street corners with one-of-a-kind buildings.

Although Schlitz built a staggering 57 tied houses between 1897 and 1905, they were not the only ones at it. This example at

E.R. Stege Chicago U.S.A.

This building is located at 24th and Western, a mere three blocks away from the Washtenaw location. Compare this logo to the examples above or below The text identifying Stege was removed at some point.

|   |

Located at the corner of 23rd and California, this is one of the most finely detailed tied houses in the entire city. The classically inspired cornice is executed in copper, as is the Stege logo inset in the pediment. The logo is surrounded by numerous terra cotta fleurs-de-lis (⚜), a symbol generally associated with the French. Perhaps it was used here as a reference to Chicago’s early history.

The pièce de maison logo executed de

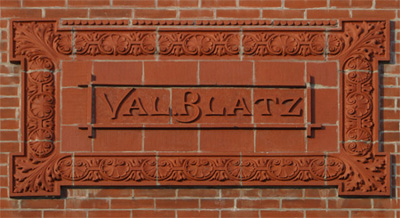

The Valentin Blatz brewery was one of the many Milwaukee-based shipping brewers that infiltrated the Chicago market early on. The company was sold to Pabst in the 1950’s, and lives on in name only, similarly

This was an exciting find. This Peter Hand tied house is less than a block away from the Blatz example, seen above. Physical evidence of the stiff nature of the competition turn of the century breweries

Right: JK

Left: The “B” here stands for Birk Brothers, a Lincoln Park-based operation which was located along the Lakewood branch railroad at Webster. They were in the brew

This tied house, built in 1910, was designed by the architectural firm of Huehl & Schmid, the firm responsible for the Medinah Temple. Although Pabst Blue Ribbon is probably preferred by patrons of the current establishment in this location, a hipster bar called Skylark

Right: Standard Brewery was located at Roosevelt and Campbell and was in business from 1892 to 1923. Unlike Birk, they did not survive Prohibition. This tied house, at Grand and Hamlin, was built in 1903 with keystones the size of a truck.

Demolished

Illinois Historic Preservation Agency.

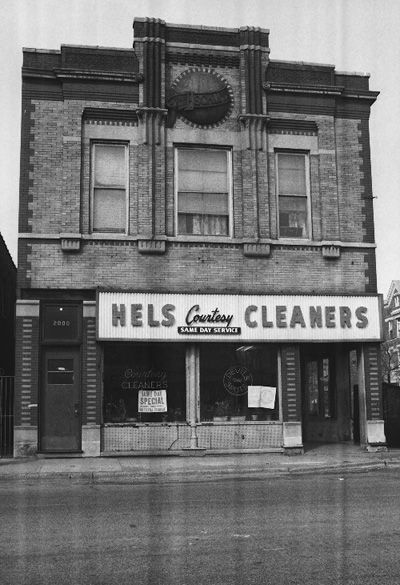

Left: 11450 S. Front, c.

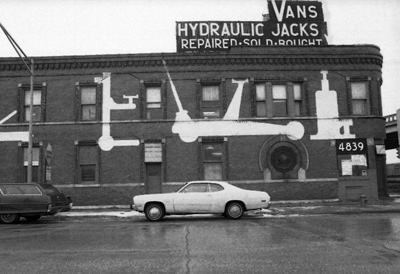

Right: 4839 W. Ogden, Cicero, c.

Checklist

This is not a complete list of Chicago’s tied houses. There are many more out there that we have not yet found, and we are always on the lookout for more.

| Brewery | Logo? | Location | Image? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlas | N | 2101 W. 18th Pl. |  | — |

| Atlas | Y | 3759 W. 26th St. |  | — |

| Atlas | N | 2500 S. Whipple |  | — |

| Atlas | N | 2202 S. Halsted |  | — |

| Atlas | N | 4012 W. Ogden |  | — |

| Birk Bros. | Y | 2147 S. Halsted |  | Skylark |

| Birk Bros. | N | 2056 N. Hoyne |  | — |

| Blatz | Y | Wolcott/Rice |  | — |

| Fortune Bros. | N | 401 S. Cicero |  | — |

| Gottfried | Y | 25th/Hamlin |  | — |

| Miller | N | 1100 W. Webster |  | — |

| Miller | N | 1404 N. Hamlin |  | — |

| Pabst | N | Ohio/Kedzie |  | — |

| Pabst | N | 120th/Halsted |  | — |

| Peter Hand | Y | Wolcott/Thomas |  | Happy Village |

| Schlitz | Y | Division/Wood |  | — |

| Schlitz | Y | 21st/Rockwell |  | — |

| Schlitz | Y | Southport/Henderson |  | Southport Lanes |

| Schlitz | Y | Southport/Belmont |  | |

| Schlitz | Y | Ewing/94th |  | Bamboo Lounge |

| Schlitz | Y | Armitage/Oakley |  | — |

| Schlitz | Y | Belmont/Leavitt |  | |

| Schlitz | Y | 114th/Front |  | — |

| Schlitz | Y | Grand/Damen |  | — |

| Schlitz | Y | 35th/Western |  | — |

| Schlitz | Y | Armitage/Damen |  | — |

| Schlitz | Y | 69th/Morgan |  | — |

| Schlitz | Y | Broadway/Winona |  | — |

| Schlitz | N | 19th/Blue Island |  | — |

| Schlitz | N | Foster/Clark |  | — |

| Schlitz | N | Diversey/Francisco |  | — |

| Schlitz | N | Diversey/Rockwell |  | — |

| Schlitz | N | California/Nelson |  | — |

| Schlitz | N | Roscoe/Racine |  | — |

| Schlitz | N | 89th/Normal |  | — |

| Standard | Y | Grand/Hamlin |  | — |

| Stege | Y | 24/Western |  | — |

| Stege | Y | 24th/Washtenaw |  | — |

| Stege | Y | 23rd/California |  | — |

No comments:

Post a Comment